Thanks to everyone who pointed me to the flub below. It was reported all over the place today.

The error occurred on One News Now, a news website run by the conservative Christian American Family Association. The site provides Christian conservative news and commentary. One of the things they do, apparently, is offer a version of the standard Associated Press news feed. Rather than just republishing it, they run software to clean up the language so it more accurately reflects their values and choice of terminology. They do so with a computer program.

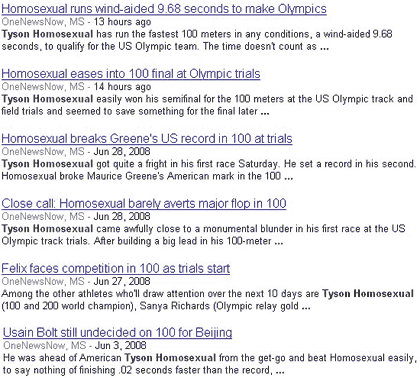

The error is a pretty straightforward variant of the clbuttic effect — a run-away filter trying to clean up text by replacing offensive terms with theoretically more appropriate ones. Among other substitutions, AFA/ONN replaced the term “gay” with “homosexual.” In this case, they changed the name of champion sprinter and U.S. Olympic hopeful Tyson Gay to “Tyson Homosexual.” In fact, they did it quite a few times as you can see in the screenshot below.

Now, from a technical perspective, the technology this error reveals is identical to the clbuttic mistake. What’s different, however, is the values that the error reveals.

AFA doesn’t advertise the fact that it changes words in its AP stories — it just does it. Most of its readers probably never know the difference or realize that the messages and terminology they are being communicated to in is being intentionally manipulated. AFA prefers the term “homosexual,” which sounds clinical, to “gay” which sounds much less serious. Their substitution, and the error it created, reflects a set of values that AFA and ONN have about the terminology around homosexuality.

It’s possible than the AFA/ONN readers already know about AFA’s values. This error provides an important reminder and shows, quite clearly, the importance that AFA gives to terminology. It reveals their values and some of the actions they are willing to take to protect them.