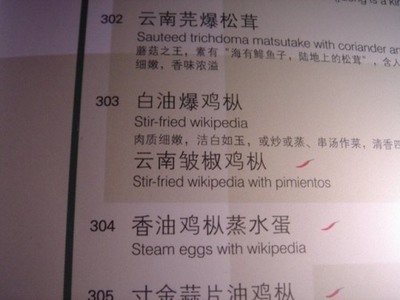

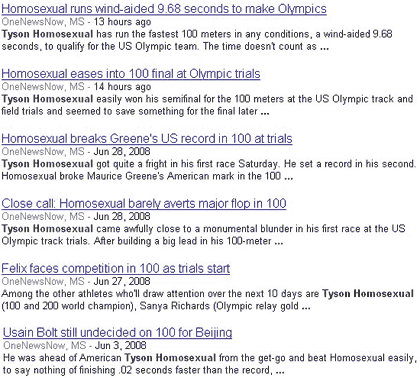

Errors reveal characteristics of the languages we use and the technologies we use to communicate them — everything from scripts and letter forms (which while very fundamental to written communication are technologies nonetheless) to the computer software we use to create and communicate text.

I’ve spent the last few weeks in Japan. In the process, I’ve learned a bit about the Japanese language; no small part of this through errors. Here’s one error that taught me quite a lot. The sentence is shown in Japanese and then followed by a translation into English:

今年から貝が胃に棲み始めました。

This year, a clam started living in my stomach.

Needless to say perhaps, this was an error. It was supposed to say:

今年から海外に住み始めました。

This year, I started living abroad.

When the sentences are translated into romaji (i.e., Japanese written in an Roman script) the similarity becomes much more clear to readers that don’t understand Japanese:

Kotoshikara kaiga ini sumihajimemashita.

Kotoshikara kaigaini sumihajimemashita.

Kotoshikara means “since this year.” Sumihajimemashita means, “has started living.” The word kaigaini means “abroad” or “overseas.” Kaiga ini (two words) means “clam in stomach.” When written phonetically in romaji, the only difference in the two sentences lie in the introduction of a word-break in the middle of “kaigaini.” Written out in Japanese, the sentences are quite different; even without understanding, one can see that more than a few of the characters in the sentences differ.

In English word spacing plays an essential role in making written language understandable. Japanese, however, is normally written without spaces between words.

This isn’t a problem in Japanese because the Japanese script uses a combination of logograms — called kanji — and phonetic characters — called hiragana and katakana or simply kana — to delimit words and to describe structure. The result, to Japanese readers, is unambiguous. Phonetically and without spaces, the two sentences are identical in either kana or romaji:

ことしからかいがいにすみはじめました。

Kotoshikarakaigainisumihajimemashita.

In purely phonetic form, the sentence is ambiguous. Using kanji, as shown in the opening examples, this ambiguity is removed. While phonetically identical, “kaigaini” (abroad) and “kaiga ini” (clam in stomach) are very different when kanji is used; they are written “海外に” and “貝が胃に” respectively and are not easily confusable by Japanese readers.

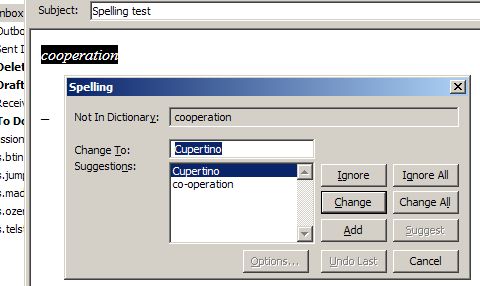

This error, and many others like it, stems from the way that Japanese text is input into computers. Because there are more than 4,000 kanji in frequent use in Japan, there simply are not enough keys on a keyboard to input kanji directly. Instead, text in Japanese is input into computers phonetically (i.e., in kana) without spaces or explicit word boundaries. Once the kana is input, users then transform the phonetic representation of their sentence or phrase into a version using the appropriate kanji logograms. To do so, Japanese computer users employ special software that contains a database of mappings of kana to kanji. In the process, this software makes educated guesses about where word boundaries are. Usually, computers guess correctly. When computers get it wrong, users need to go back and tweak the conversion by hand or select from other options in a list. Sometimes, when users are in a rush, they use an incorrect kana to kanji conversion. It would be obvious to any Japanese computer users that this is precisely what happened in the sentence above.

This type of error has few parallels in English but is extremely common in Japanese writing. The effects, like this one, are often confusing or hilarious. For a Japanese reader, this error reveals the kana to kanji mapping system and the computer software that implements it — nobody would make such a mistake with a pen and paper. For a person less familiar with Japanese, the error reveals a number of technical particularities about the Japanese writing system and, in the process, about the ways in Japanese differs from other languages they might speak.