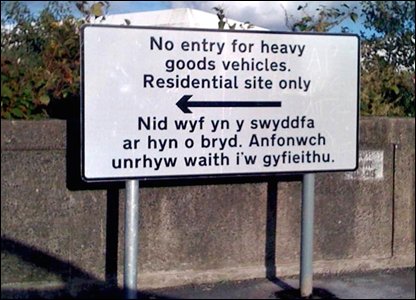

Last year, I talked about some of the dangers of machine translation that resulted in a Chinese restaurant advertised as “Translate Server Error” and another restaurant serving “Stir Fried Wikipedia.” This article from the BBC a couple months ago shows that embarassing translation errors are hardly limited to either China or to machine translation systems.

The English half of the sign is printed correctly and says, “No entry for heavy goods vehicles. Residential site only.” Clearly enough, the point of the sign is to prohibit truck drivers from entering a residential neighborhood.

Since the sign was posted in Swansea, Wales, the bottom half of the sign is written in Welsh. The translation of the Welsh is, “I am not in the office at the moment. Send any work to be translated.”

It’s not too hard to piece together what happened. The bottom half of the sign was supposed to be a translation of the English. Unfortunately, the person ordering the sign didn’t speak Welsh. When he or she sent it off to be translated, they received a quick response from an email autoresponder explaining that the email’s intended recipient was temporarily away and that they would be back soon — in Welsh.

Unfortunately, the representative of the Swansea council thought that the autoresponse message — which is coincidentally, about the right length — was the translation. And onto the sign it went. The autoresponse system was clearly, and widely, revealed by the blunder.

One thing we can learn from this mishap is simply to be wary of hidden intermediaries. Our communication systems are long and complex; every message passes through dozens of computers with a possibility of error, interception, surveillance, or manipulation at every step. Although the representative of the Swansea council thought they were getting a human translation, they, in fact, never talked to a human at all. Because the Swansea council didn’t expect a computerized autoresponse, they didn’t consider that the response was not sent by the recipient.

Another important lesson, and one also present in the Chinese examples, is that software needs to give users responses in the language they are interacting in to be interpreted correctly. In the translation context where users plan to use, but may not understand, their program’s output, this is often impossible. That’s why when a person has someone, or some system, translate into a language they do not speak, they open themselves up to these types of errors. If a user does not understand the output of a system they are using, they are put completely at the whim of that system. The fact that we usually do understand our technology’s output provides a set of “sanity checks” that can keep this power in check. We are so susceptible to translation errors because these checks are necessarily removed.