SSL stands for “Secure Sockets Layer” and refers to a protocol for using the web in a secure, encrypted, manner. Every time you connect to a website with an address prepended with https://, instead of just http://, you’re connecting over SSL. Almost all banks and e-commerce sites, for example, use SSL exclusively.

SSL helps provide security for users in at least two ways. First, it helps keep communication encoded in such a way that only you and the site you are communicating with can read it. The Internet is designed in a way that makes messages susceptible to eavesdropping; SSL helps prevent this. But sending coded messages only offer protection if you trust that the person you are communicating in code with really is who they say they are. For example, if I’m banking, I want to make sure the website I’m using really is my bank’s and not some phisher trying to get my account information. The fact that we’re talking in a secret code will protect me from eavesdroppers but won’t help me if I can’t trust the person I’m talking in code with.

To address this, web browsers come with a list of trusted organizations that verify or vouch for websites. When one of these trusted organizations vouches that a website really is who they say they are, they offer what is called a “certificate” that attests to this fact. A certificate for revealingerrors.com would help users verify that that they really are viewing Revealing Errors, and not some intermediary, impostor, or stand-in. If someone were redirect traffic meant for Revealing Errors to an intermediary, users connecting using SSL would get an error message warning them that the certificate offered is invalid and that something might be awry.

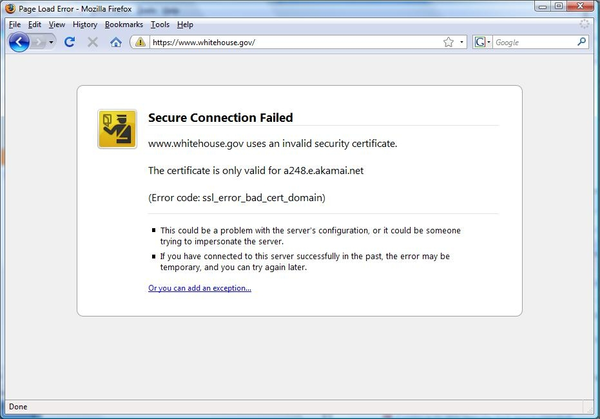

That bit of background provides the first part of this explanation for this error message.

In this image, a user attempted to connect to the Whitehouse.gov website over SSL — visible from the https in the URL bar. Instead of a secure version of the White House website, however, the user saw an error explaining that the certificate attesting to the identity of the website was not from the United States White House, but rather from some other website called a248.e.akamai.net.

This is a revealing error, of course. The SSL system, normally represented by little more than a lock icon in the status bar of a browser, is thrust awkwardly into view. But this particularly revealing error has more to tell. Who is a248.e.akamai.net? Why is their certificate being offered to someone trying to connect to the White House website?

a248.e.akamai.net is the name of a server that belongs to a company called Akamai. Akamai, while unfamiliar to most Internet users, serves between 10 and 20 percent of all web traffic. The company operates a vast network of servers around the world and rents space on these servers to customers who want their websites to work faster. Rather than serving content from their own computers in centralized data centers, Akamai’s customers can distribute content from locations close to every user. When a user goes to, say, Whitehouse.gov, their computer is silently redirected to one of Akamai’s copies of the Whitehouse website. Often, the user will receive the web page much more quickly than if they had connected directly to the Whitehouse servers. And although Akamai’s network delivers more 650 gigabits of data per second around the world, it is almost entirely invisible to the vast majority of its users. Nearly anyone reading this uses Akamai repeatedly throughout the day and never realizes it. Except when Akamai doesn’t work.

Akamai is an invisible Internet intermediary on a massive scale. But because SSL is designed to detect and highlight hidden intermediaries, Akamai has struggled to make SSL work with their service. Although Akamai offers a service designed to let their customers use Akamai’s service with SSL, many customers do not take advantage of this. The result is that SSL remains one place where, through error messages like the one shown above, Akamai’s normally hidden network is thrust into view. An attempt to connect to a popular website over SSL will often reveal Akamai. The White House is hardly the only victim; Microsoft’s Bing search engine launched with an identical SSL error revealing Akamai’s behind-the-scenes role.

Akamai plays an important role as an intermediary for a large chunk of all activity online. Not unlike Google, Akamai has an enormous power to monitor users’ Internet usage and to control or even alter the messages that users send and receive. But while Google is repeatedly — if not often enough — held to the fire by privacy and civil liberties advocates, Akamai is mostly ignored.

We appreciate the power that Google has because they are visible — right there in our URL bar — every time we connect to Google Search, GMail, Google Calendar, or any of Google’s growing stable of services. On the other hand, Akamai’s very existence is hidden and their power is obscured. But Akamai’s role as an intermediary is no less important due its invisibility. Errors provide one opportunity to highlight Akamai’s role and the power they retain.