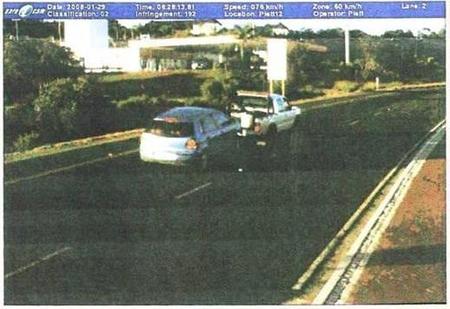

In the past, I’ve talked about how certain errors can reveal a human in what we may imagine is an entirely automated process. I’ve also shown quite a few errors that reveal the absence of a human just as clearly. Here’s a photograph attached to a speeding ticket given by an automated speed camera that shows the latter.

The Daily WTF published this photograph which was sent in by Thomas, one of their readers. The photograph came attached to this summons which arrived in the mail and explained that Thomas had been caught traveling 72 kilometers per hour in a 60 KPH speed zone. The photograph above was attached as evidence of his crime. He was asked to pay a fine or show up in court to contest it.

Obviously, Thomas should never have been fined or threatened. It’s obvious from the picture that Thomas’ car is being towed. Somebody was going 72 KPH but it was the tow-truck driver, not Thomas! Anybody who looked at the image could see this.

In fact, Thomas was the first person to see the image. The photograph was taken by a speed camera: a radar gun measured a vehicle moving in excess of the speed limit and triggered a camera which took a photograph. A computer subsequently analyzed the image to read the license plate number and look up the driver in a vehicle registration database. The system then printed a fine notice and summons notice and mailed it to the vehicle’s owner. The Daily WTF editor points out that proponents of these automated systems often guarantee human oversight in the the implementation of these systems. This error reveals that the human oversight in the application of this particular speed camera is either very little or none and all.

Of course, Thomas will be able to avoid paying the fine — the evidence that exonerates him is literally printed on his court summons. But it will take work and time. The completely automated nature of this system, revealed by this error, has deep implications for the way that justice is carried out. The system is one where people are watched, accused, fined, and processed without any direct human oversight. That has some benefits — e.g., computers are unlikely to let people of a certain race, gender, or background off easier than others.

But in addition to creating the possibilities of new errors, the move from a human to a non-human process has important economic, political, and social consequences. Police departments can give more tickets with cameras — and generate more revenue — than they could ever do with officers in squad cars. But no camera will excuse a man speeding to the hospital with a wife in labor or a hurt child in the passanger seat. As work to rule or “rule-book slowdowns” — types of labor protests where workers cripple production by following rules to the letter — show, many rules are only productive for society because they are selectively enforced. The complex calculus that goes into deciding when to not apply the rules, second nature to humans, is still impossibly out of reach for most computerized expert systems. This is an increasingly important fact we are reminded of by errors like the one described here.