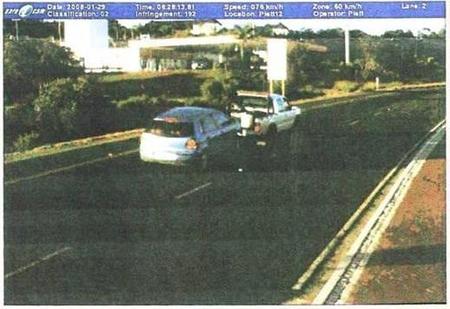

In the past, I’ve talked about how certain errors can reveal a human in what we may imagine is an entirely automated process. I’ve also shown quite a few errors that reveal the absence of a human just as clearly. Here’s a photograph attached to a speeding ticket given by an automated speed camera that shows the latter.

The Daily WTF published this photograph which was sent in by Thomas, one of their readers. The photograph came attached to this summons which arrived in the mail and explained that Thomas had been caught traveling 72 kilometers per hour in a 60 KPH speed zone. The photograph above was attached as evidence of his crime. He was asked to pay a fine or show up in court to contest it.

Obviously, Thomas should never have been fined or threatened. It’s obvious from the picture that Thomas’ car is being towed. Somebody was going 72 KPH but it was the tow-truck driver, not Thomas! Anybody who looked at the image could see this.

In fact, Thomas was the first person to see the image. The photograph was taken by a speed camera: a radar gun measured a vehicle moving in excess of the speed limit and triggered a camera which took a photograph. A computer subsequently analyzed the image to read the license plate number and look up the driver in a vehicle registration database. The system then printed a fine notice and summons notice and mailed it to the vehicle’s owner. The Daily WTF editor points out that proponents of these automated systems often guarantee human oversight in the the implementation of these systems. This error reveals that the human oversight in the application of this particular speed camera is either very little or none and all.

Of course, Thomas will be able to avoid paying the fine — the evidence that exonerates him is literally printed on his court summons. But it will take work and time. The completely automated nature of this system, revealed by this error, has deep implications for the way that justice is carried out. The system is one where people are watched, accused, fined, and processed without any direct human oversight. That has some benefits — e.g., computers are unlikely to let people of a certain race, gender, or background off easier than others.

But in addition to creating the possibilities of new errors, the move from a human to a non-human process has important economic, political, and social consequences. Police departments can give more tickets with cameras — and generate more revenue — than they could ever do with officers in squad cars. But no camera will excuse a man speeding to the hospital with a wife in labor or a hurt child in the passanger seat. As work to rule or “rule-book slowdowns” — types of labor protests where workers cripple production by following rules to the letter — show, many rules are only productive for society because they are selectively enforced. The complex calculus that goes into deciding when to not apply the rules, second nature to humans, is still impossibly out of reach for most computerized expert systems. This is an increasingly important fact we are reminded of by errors like the one described here.

If the recipient of the ticket has to take time off of work to fight the ticket, driving to a courthouse which may be some distance away, paying the ticket may actually be cheaper. There’s no justice to be had here.

The most important problem here is that you are guilty unless proven otherwise. Of course, this assumption is already made for traffic fines. It would not be economic to summon every offender to court and find out if he really did something wrong. As traffic tickets are correct most times, this procedure saves all participants’ time.

However, once you automate the process you get more false positives like the example above. How many false accusations are acceptable for a justice system? Refuting wrong allegations takes time, money, and some knowledge of the justice system. Thus, some groups (foreigners, homeless, illiterate, etc.) may get less justice.

I’m pretty sure you can also automate camera detection of people dropping rubbish onto public ground.

Combine this with cell phone tracking and you can extremely increase a city’s revenue.

And maybe you’ll once receive a notification “Image and motion analysis reveals that you were molesting a child on $DATE at $PLACE. Your name has been entered into $PUBLIC_DATABASES. If you do not agree with this decision please hand in form 24029-B and a recent psychological report.”

James Vasile just posted this link on his blog:

http://hackervisions.org/?p=27

It’s everything I should have said in this post and didn’t. Thanks James.

I don’t know if what I was told, or my recollection, are accurate, but I remember being told when I was young that these sorts of systems were illegal (in the US, at the time), because the Constitution granted us the right to face our accuser(s) and in an automated world there were no accusers. If that’s the case then when/how did this change?

In theory I have no qualms with these sorts of systems, but the example above clearly shows that theory doesn’t equal actual. I also like the idea of discretion, but I think that could be passed onto the courts…

Court: “Mr. X. the spy-bot caught you doing 72 in a 50. What do you plead?”

Mr X: “Guilty, your Honor.”

Court: “Why were you exceeding the speed limit Mr X.?”

Mr X: “My wife was well into labor and I could see my child’s head starting to breach. I thought it prudent to seek medical care ASAP.”

Court: “Very well, I find that the defendant was guilty of speeding and owes 1 cent in damages.”

This isn’t exactly ideal, but if we’re going to have robots effectively trying and convicting us we need SOME discretion in the system.

Thanks, Mako.

Jeremy, it seems to me that the speed trap camera isn’t the accuser here. The accuser is whatever agency puts up the cameras. The photo is just evidence. Bad evidence in this case, but that’s as far as it goes.