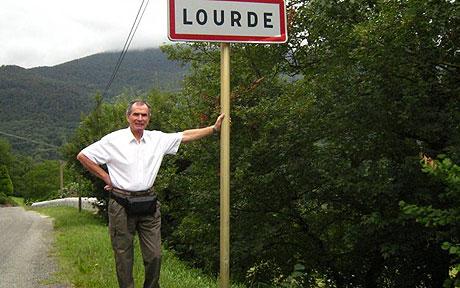

The Telegraph ran an article about a sizable — and growing — number of Catholic pilgrims arriving in a small village in the Pyrenean foothills. With 94 residents, the town has no hotels or shops — a fact that has left some of the new arrivals a bit confused. The town does have a small statue of the Virgin Mary which some pilgrims have worshiped at. Most pilgrims have noted that the town seems curiously quiet for Catholicism’s third largest pilgrimage site.

The village is Lourde. Without an “s”. The pilgrims, of course, are looking for Lourdes. The statue some pilgrims have prostrated themselves in front of is not the famous Statue of Our Lady at the Grotto of Massabielle but a simple village statue of the virgin. Lourde is 92 kilometers (57 miles) to the east of the larger and more famous city with the very similar name.

Given the similar names, pilgrims have apparently been showing up at Lourde for as long as the residents of the smaller village can remember. But villagers report a very large up-tick in confused pilgrims in recent years. To blame, apparently, is the growing popularity of GPS navigation systems.

Pilgrims have typed in “L-O-U-R-D-E” in their GPS navigation devices and forgotten the final “S”. Indeed, using the clunky on-screen keyboards and automatic completion functionality, it’s often much easier to type in the name of the tiny village than the name of the more likely destination. One letter and only 92 kilometers away in the same country, it’s an easy mistake to make because the affordances of many GPS navigation systems make it slightly easier to ask to go to Lourde than to Lourdes. Apparently, twenty or so cars of pilgrims show up in Lourde each day. Sometimes carrying as many people as live in the town of Lourde itself!

The GPS navigation systems, of course, will happy route drivers to either city and do not know or care that Lourde is rarely the location a driver navigating from across Europe wants. The GPS is designed to show drivers their next turn so a driver won’t know they’re off course until they reach their destination. The systems assume that destinations were entered correctly. A human navigator asked for directions would never point a person to the smaller village. Indeed, they would probably not know it even exists.

A municipal councilor in Lourde suggested that, “the GPS is not at fault. People are.” Of course, she’s correct. Pilgrims typed in the name of their destination incorrectly. But the reason there’s an increase in people making this particular mistake is because the technology people use to navigate in their cars has changed dramatically over the last decade in a way that makes this mistake more likely. A dwindling number of people pore over maps or ask a passer-by or a gas station attendant for directions. On the whole, navigation has become more effective and more convenient. But not without trade-offs and costs.

GPS technology frames our experience of navigation in ways that are profound, even as we are usually take it for granted. Unlike a human, the GPS will never suggest a short detour that leads us to a favorite restaurant or a beautiful vista we’ll be driving by just before sunset. As in the case of Lourde, it will make mistakes no human would (the reverse is also true, of course). In this way, the twenty cars of confused pilgrims showing up in Lourde each day can remind us of the power that technologies have over some of the little tasks in our lives.