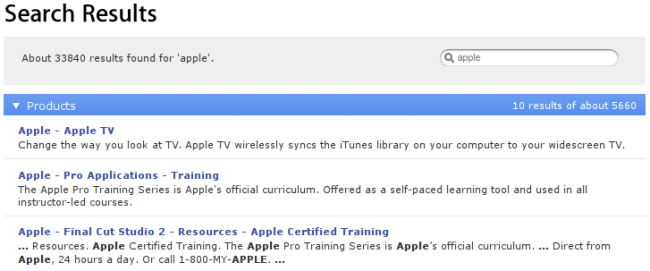

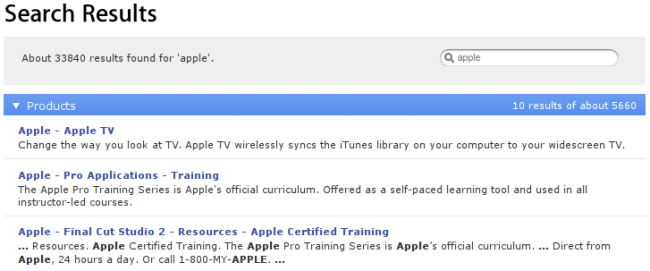

Blogger Jordan Wiens recently noticed a funny thing about the Apple website. When one tries to search for “applescript” (Apple’s scripting and automation product) on Apple’s website, they end up with this search result:

Until the issue is fixed, you can see for yourself by navigating to http://www.apple.com/search/?q=applescript.

On the search result page, the Apple search software seems to change the term “applescript” into “apple.” A search for the term “apple” on the Apple website is, as one might imagine, not a particularly useful way to find information about Applescript. To most users, this error is confounding. To a trained eye, it reveals an overzealous security system attempting to prevent what’s called cross-site scripting or XSS — a way that spammers, phishers, and nefarious system-crackers can sneakily work around privacy and security systems in web browsers by exploiting two features of modern web browsers.

First, through the use of a programming language called Javascript, many web pages run small computer programs inside users’ browsers. These Javascript programs allow for applications that are more responsive than would have been possible before (think Google Maps for a good example). Running random programs is risky, of course. To protect users and their privacy, web browsers limit Javascript programs in several ways. One common technique is to limit access granted to a Javascript program from a given website to information from the site the Javascript originated at. This security system is designed to bar one website’s programs from accessing and relaying sensitive information, like login information or credit card numbers, from another website.

Second, a large number of applications allow input from users that is subsequently displayed on web pages. This can come in the form of edits and additions to Wikipedia pages, comments on forums, articles, or blogs, or even the fact that when you run a web search, the search terms are displayed back to you at the top of your page.

A security vulnerability, it turns out, lies in the combination of the two features. This vulnerability, XSS, happens when a nefarious user embeds small Javascript programs in input (e.g., a comment) which is run each time a page is subsequently viewed. Masquerading to the browser as a legitimate script created by the website creator, these programs can access sensitive information from the website stored on the user’s computer (e.g., login information) and then send this information to the author of the script without the violated user’s permission or knowledge.

When an attacker executes an XSS attack, they do so by trying to include Javascript in input that will be displayed to the user. This usually comes in the form of:

<script>some code send to private information</script>

In HTML, the “<script>” and “</script>” tags signify to the web browser that the text between is a program to be run.

XSS has become a large problem. To combat and prevent it, web developers take great care to protect their users and their applications from attacks by blocking, removing, or disabling attempts to include programs in user input. One frequently employed method of doing so is to simply remove the “<script>” tags that cause programs to be run. Without the tags, malicious code may remain, but will never be executed on users’ computers.

With this knowledge of XSS we can begin to understand the puzzling behavior of Apple’s website. By trying several other searches, we can confirm that Apple’s search engine is, in fact, removing all mentions of the term “script” from input to the site. The system is almost certainly designed to block XSS. While it is likely to succeed in doing so, the side effects, in the case of users searching for Applescript, are extremely inconvenient.

Through the error, Apple reveals their overzealous system designed to prevent XSS. Those who dig deeper to understand the source of this initially baffling behavior can gain new respect for implicit trust that that our browsers give to code on the websites we visit and the ways in which this trust can be abused.

In all likelihood, we have all been the victims of XSS attacks as users — although most of us have been lucky enough to avoid divulging sensitive information in the process. Apple’s error represents “collateral damage” in a a war fought between crackers, spammers, phishers on one side and web applications developers on the other. While we are rarely aware of it, this battle affects the way our web applications are designed and the features they do, and do not, include. We are, indirectly, affected by XSS even when we’re not looking for information on Applescript. By revealing one anti-XSS security system, Apple’s mistep points to that fact.