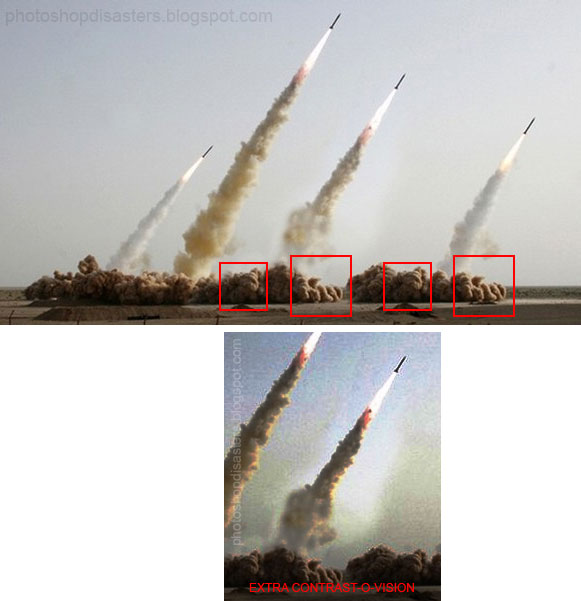

Earlier in the summer, Iran released this image to the international community — purportedly a photograph of rocket tests carried out recently.

There was an interesting response from a number of people that pointed out that the images appeared to have been manipulated. Eventually, the image ended up on the blog Photoshop Disasters (PsD) who released this marked up image highlighting the fact that certain parts of the image seemed similar to each other. Identical in fact; they had been cut and pasted.

The blog joked that the photos revealed a “shocking gap in that nation’s ability to use the clone tool.”

The clone tool — sometimes called the “rubber stamp tool” — is a feature available in a number of photo-manipulation programs including Adobe Photoshop, GIMP and Corel Photopaint. The tool lets users easily replace part of a picture with information from another part. The Wikipedia article on the tool offers a good visual example and this description:

The applications of the cloning tool are almost unlimited. The most common usage, in professional editing, is to remove blemishes and uneven skin tones. With a click of a button you can remove a pimple, mole, or a scar. It is also used to remove other unwanted elements, such as telephone wires, an unwanted bird in the sky, and a variety of other things.

Of course, the clone tool can also be used to add things in — like the clouds of dust and smoke at the bottom of the images of the Iranian test. Used well, the clone tool can be invisible and leave little or no discernible mark. This invisible manipulation can be harmless or, as in the case of the Iranian missiles, it can used for deception.

The clone tool makes perfect copies. Too perfect. And these impossibly perfect reproductions can becoming revealing errors. Through its introduction of unnatural verisimilitude within an image, the clone introduces errors. In doing so, it can reveal both the person manipulating the image and their tools. Through their careless use of the tool, the Iranian government’s deception, and their methods, were revealed to the world.

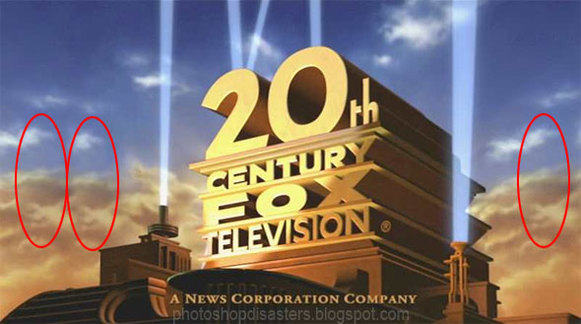

But the Iranian government is hardly the only one caught manipulating images through careless use of the clone tool. Here’s an image, annotated by PsD again, of the 20th Century Fox Television logo with “evident clone tool abuse!”

And here’s an image from Brazilian Playboy where an editor using a clone tool has become a little overzealous in their removal of blemishes.

Now we’re probably not shocked to find out that Playboy deceptively manipulates images of their models — although the resulting disregard for anatomy drives the extreme artificially of their productions home in a rather stark way.

In aggregate though, these images (a tiny sample of what I could find with a quick look) help speak to the extent of image manipulation in photographs that, by default, most of us tend to assume are unadulterated. Looking for the clone tool, and for other errors introduced by the process of image manipulation, we can get a hint of just how mediated the images we view the world are — and we have reason to be shocked.

Here’s a final example from Google maps that shows the clear marks of the clone tool in a patch of trees — obviously cloned to the trained eye — on what is supposed to be an unadulterated satellite image of land in the Netherlands.

Apparently, the surrounding area is full of similar artifacts. Someone has been edited out and papered over much of the area — by hand — with the clone tool because someone with power is trying to hide something visible on that satellite photograph. Perhaps they have a good reason for doing so. Military bases, for example, are often hidden in this way to avoid enemy or terrorist surveillance. But it’s only through the error revealed by sloppy use of the clone tool that we’re in any position to question the validity of these reasons or realize the images have been edited at all.